By Roxanne Reid

If you stay at Twyfelfontein Country Lodge in Kunene (Damaraland), Namibia, there’s lots to see and do in the area – like the Organ Pipes, Twyfelfontein engravings, Petrified Forest and Damara Living Museum. You can read more about the lodge and sights in my blog post here. But whatever you do, don’t miss a nature drive to see desert elephants.

If you stay at Twyfelfontein Country Lodge in Kunene (Damaraland), Namibia, there’s lots to see and do in the area – like the Organ Pipes, Twyfelfontein engravings, Petrified Forest and Damara Living Museum. You can read more about the lodge and sights in my blog post here. But whatever you do, don’t miss a nature drive to see desert elephants.

We set out late afternoon with guide Lukas Paulus from Twyfelfontein Country Lodge to explore the ephemeral Aba Huab and Huab rivers in the Doro Nawas Conservancy. We marvelled at layers of beautiful mountains, silky grass rippling in a light breeze, the feeling of freedom out on the plains.

You can expect to see changing landscapes and fascinating plants. Take the bizarre welwitschia with its two ribbons of leaves, for instance. Even though the plants can survive for more than 1000 years, the leaves are always the original ones; they just grow longer and more tattered by the wind. A guide once told us that a good way to estimate its age is to look at the stem base in the middle: each 10cm of diameter equates to 100 years.

You’ll also see lots of euphorbias, commonly known as milkbush. The latex is poisonous, although rhinos and kudus seem to be able to eat the stems without ill effect. In general, it’s the flowers and fruit that provide food for animals like steenbok and ground squirrels.

Lukas also told us about medicinal uses of other plants like mopane, and that the green hair tree, which stays green when all around it is brown and dry, can help springbok survive tough times.

There are fairy circles to admire too – perfectly symmetrical bare circles of one to three metres in diameter, inside of which not a blade of grass grows. Various theories have been suggested for these intriguing formations, from the romantic (fairies) to the ridiculous (UFOs), but the real reason is termites. You can read more about them in my blog post NamibRand: fairy circles and dark skies.

There are fairy circles to admire too – perfectly symmetrical bare circles of one to three metres in diameter, inside of which not a blade of grass grows. Various theories have been suggested for these intriguing formations, from the romantic (fairies) to the ridiculous (UFOs), but the real reason is termites. You can read more about them in my blog post NamibRand: fairy circles and dark skies.

For the rest, we sat back and enjoyed the nodding swathes of golden grass, the changing geology from red sandstone near the lodge to volcanic black granite and blue-grey mountains stretching across the horizon in the distance. Every turn of the sand road revealed a new vista to marvel at.

Where are the desert elephants?

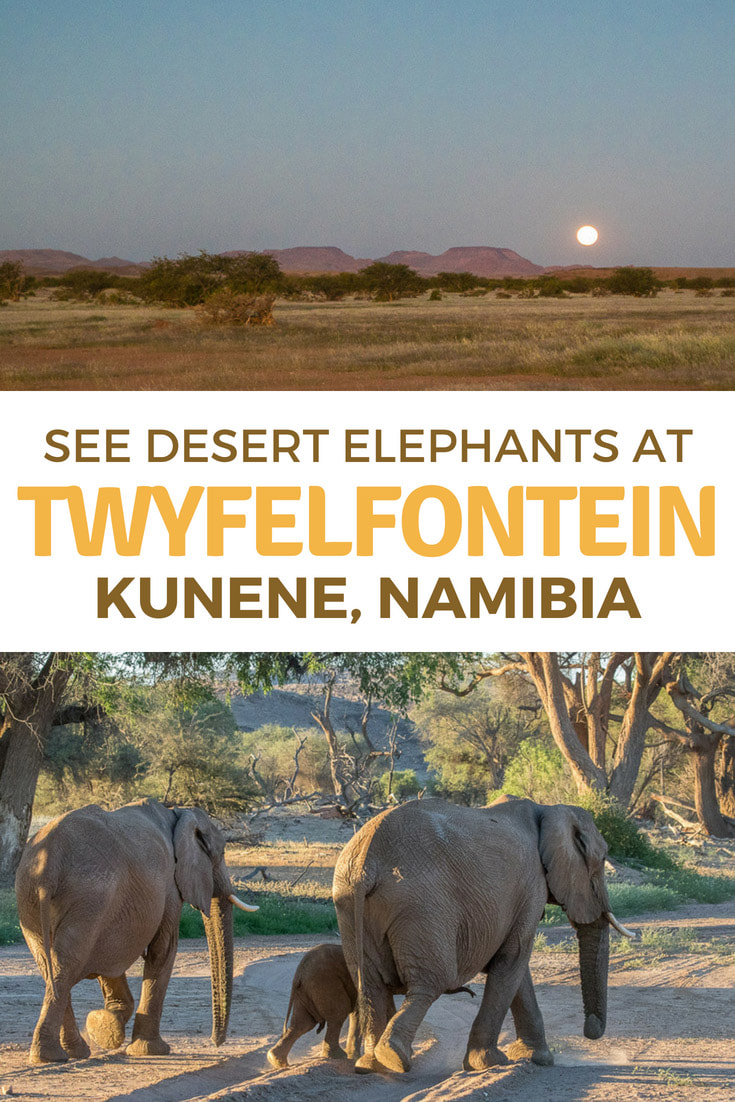

But now it was after 17:00. We’d been moving for 90 minutes and I was beginning to despair of finding any desert elephants before dark. Then we spotted fresh tracks and fresh dung. Excitement mounted in a chase against the fading light. We bounced around the same area twice in the vehicle, finally clapping eyes on six of them feeding on dried branches with a loud crackling noise.

But now it was after 17:00. We’d been moving for 90 minutes and I was beginning to despair of finding any desert elephants before dark. Then we spotted fresh tracks and fresh dung. Excitement mounted in a chase against the fading light. We bounced around the same area twice in the vehicle, finally clapping eyes on six of them feeding on dried branches with a loud crackling noise.

The adults were very focused on packing in the nutrition, but a calf of about four months old entertained us by trying to pick up and carry a stick in a trunk not yet fully under his control, finding a little embankment and having a lie down, then struggling to get up again. He also enjoyed a few interludes of suckling, floppy little trunk curled back out of the way.

The elephants went about their lives undisturbed while I sat there breathless and entranced. Thirty minutes went by in a flash. Then they started to move away, the golden sunlight of late afternoon rim lighting their bottoms as they ambled into the trees.

Lucas explained that there are about 25-30 elephants in this area, and sometimes they get much closer to the lodge than this. But the guides keep their eyes and ears open, so they usually know where they have last been seen. If you’re keen to see desert elephants, this is a good place to try to fulfil your wish.

Desert elephant adaptations

We may call them desert elephants, which occur only in Namibia and Mali in North Africa, but they are not a subspecies of the normal African elephant we know from Etosha or Chobe national parks. More correctly, we should refer to them as desert-adapted elephants because they’ve developed some ingenious adaptations to survive in this harsh and arid environment.

Desert elephant adaptations

We may call them desert elephants, which occur only in Namibia and Mali in North Africa, but they are not a subspecies of the normal African elephant we know from Etosha or Chobe national parks. More correctly, we should refer to them as desert-adapted elephants because they’ve developed some ingenious adaptations to survive in this harsh and arid environment.

- They rarely push over trees as they do elsewhere, preferring to be able to return to them as a source of nutrition. Instead, they just break off branches.

- They usually keep to small family groups rather than big herds, to maximise their chances of finding enough food.

- They have less bulky bodies, possibly from less food than other elephants.

- They have wider feet that help them to walk in the soft sand, in much the same way as deflating your 4x4’s tyres to give a larger surface in contact with the sand helps you not to get stuck.

- They can walk up to 200km in 24 hours in their search for water.

- Unlike other elephants, which can drink as much as 160 litres of water every single day, desert-adapted elephants in Namibia drink only every three to four days.

- They can store water in what is called a pharyngeal pouch behind the base of their tongues. This holds a whopping 7 to 14 litres of water, allowing them to travel greater distances to the next source of water. They use the tip of their trunk to get to it, and will share it with calves on long journeys. Although all African elephants have this pouch, it’s rarely used when water is easy to find.

What a thrill to see some of these resourceful creatures.

Sunset and a night drive

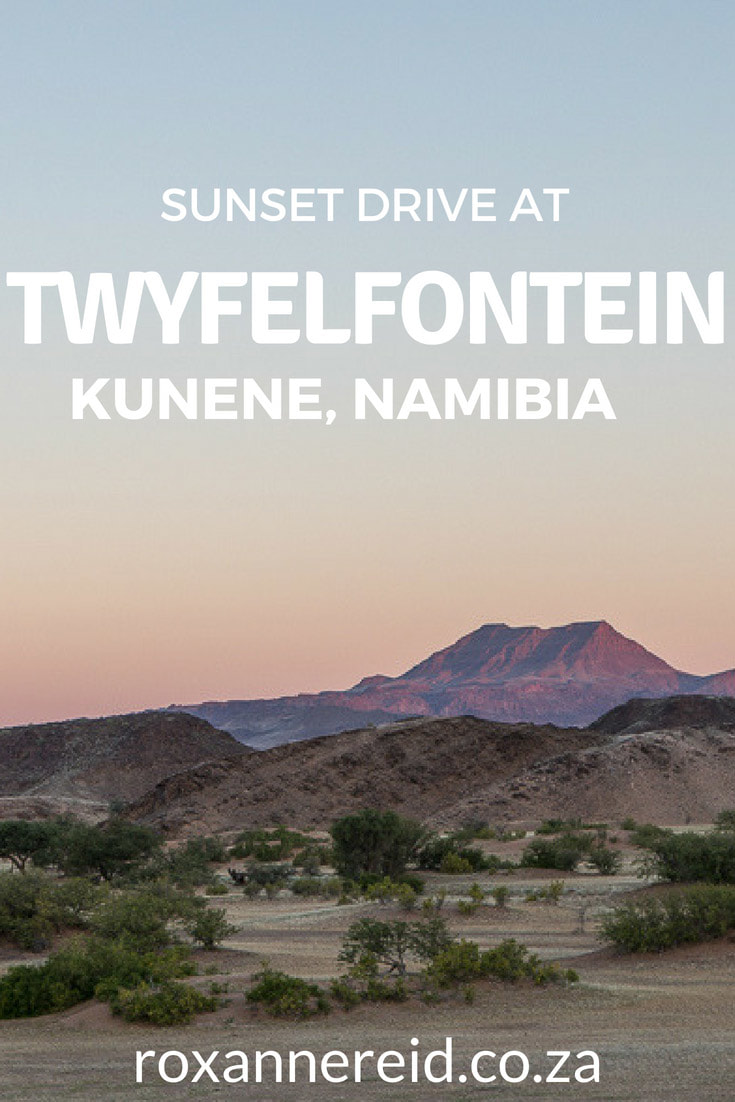

After all the excitement of seeing desert-adapted elephants, Lukas stopped on a dune so we could watch the sunset and enjoy sundowners before starting the long drive back to the lodge.

After all the excitement of seeing desert-adapted elephants, Lukas stopped on a dune so we could watch the sunset and enjoy sundowners before starting the long drive back to the lodge.

Although we didn’t spot brown hyena or aardwolf as we’d hoped, we did stop to listen to the clicking sound of barking geckoes piercing the encroaching darkness, then drove on grinning as a full moon, buttery and bright, climbed into the sky ahead of us. Desert elephants, a Namibian sunset, barking geckoes and the rise of a full moon – our hearts were full.

Like it? Pin this image!

Like it? Pin this image!

You may also enjoy

Twyfelfontein Country Lodge, Namibia: 8 reasons to visit

Highlights of Damaraland and Kaokoveld, Namibia

Copyright © Roxanne Reid - No words or photographs on this site may be used without permission from roxannereid.co.za

Twyfelfontein Country Lodge, Namibia: 8 reasons to visit

Highlights of Damaraland and Kaokoveld, Namibia

Copyright © Roxanne Reid - No words or photographs on this site may be used without permission from roxannereid.co.za